You might think the tiny muscles around your ears are just for wiggling—a quirky party trick inherited from ancient ancestors. But new research found these muscles spring to life when you’re trying to listen, like untangling a conversation in a noisy café.

Why it matters

Your ear muscles might secretly track how hard your brain is working to hear.

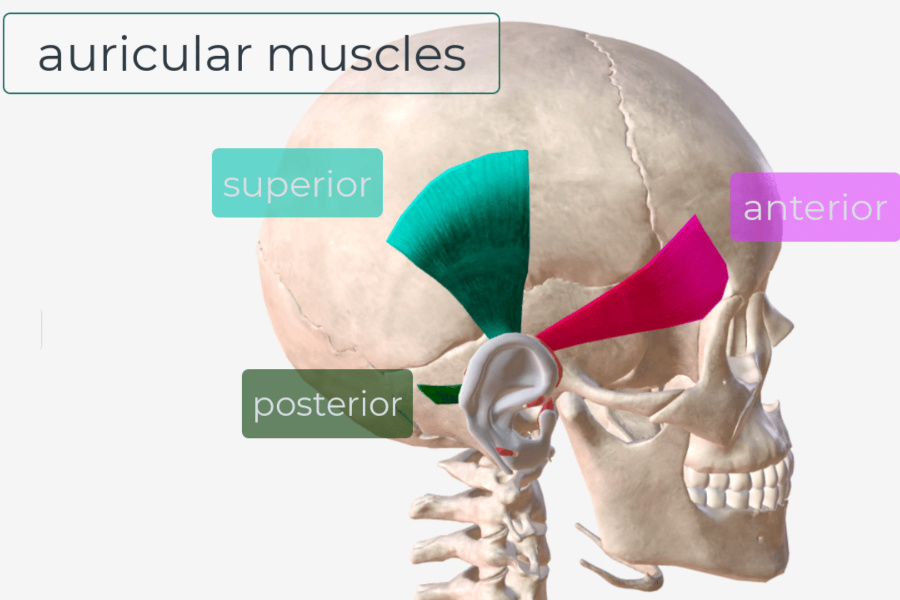

- Humans have three auricular muscles, which our ancestors used to swivel their ears like cats or dogs.

- Though mostly vestigial, scientists have found that the superior auricular muscle activates during tough listening tasks, like focusing on an audiobook with distracting background noise.

- This could help objectively measure listening effort, a breakthrough for hearing research.

"There are three large muscles which connect the auricle to the skull and scalp and are important for ear wiggling. These muscles, particularly the superior auricular muscle, exhibit increased activity during effortful listening tasks.” —Andreas Schröer, PhD, first author of the study, Saarland University

The backstory

Millions of years ago, humans relied on moving their ears to better capture sounds. This ability was supported by our auricular muscles. They helped change the shape of the outer ear to funnel sounds towards the eardrum.

As time went on and we became more reliant on visual and vocal communication, we stopped using them, and for years, scientists believed that our ear muscles were now useless, except, of course, for ear wiggling.

By the numbers

The study involved 20 people, all without hearing issues.

- Each participant underwent 12 five-minute trials, experiencing different listening conditions. These conditions were designed to progressively increase the difficulty of the listening task, forcing the participants to try hard to listen.

- Scientists noted that the superior auricular muscles activated more as the difficulty increased, whereas the posterior auricular muscles responded more to the direction of sounds.

The takeaway

While we don’t move our ears like our ancestors could, the auricular muscles still have a hidden job to do when focusing on listening.

- The research suggests that these muscles could give scientists an objective way to track listening effort.

- While muscle activity signals effort, the ear movements are imperceptible. Still, even subtle auricle shifts might aid sound localization.

- Future studies will explore how these findings translate to diverse groups of people, including those with hearing loss, to determine if these little muscles may play a role in helping them to hear.

For now, these vestigial ear muscles are a quiet clue to how our brains cope with modern noise. Our ears work harder than we think—even if they’re not moving.