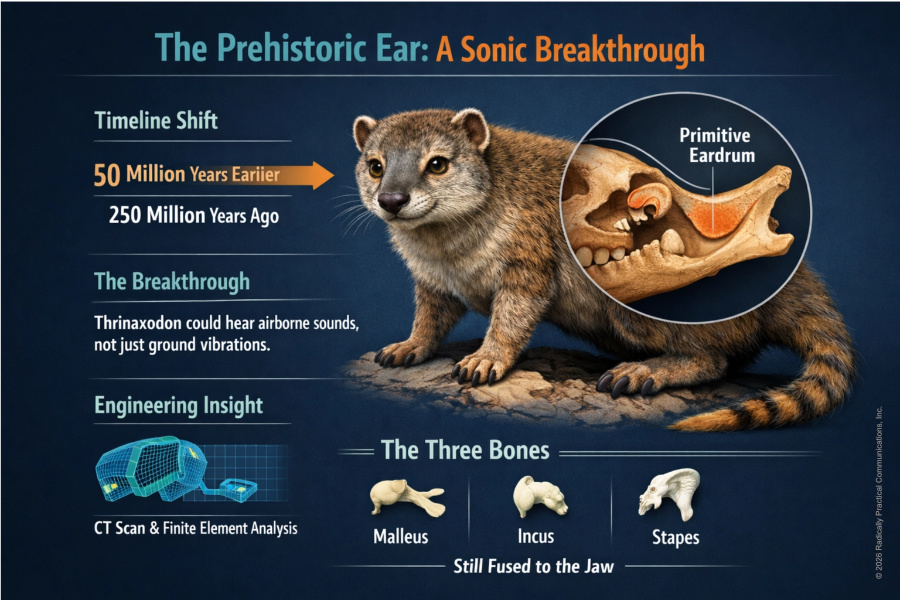

Forget what you knew about when mammals developed modern hearing. New research pushes that milestone back 50 million years, to a creature that lived 250 million years ago, just as the age of dinosaurs began.

Why it matters

Hearing airborne sounds — rustling leaves, distant footsteps, predator calls — gave early mammals a survival edge in a predator-dominated world. That advantage emerged earlier than scientists thought, rewriting our understanding of mammal evolution.

The big picture

Thrinaxodon liorhinus had a membrane across a hooked structure on its jawbone that functioned as an eardrum.

-

Engineering simulations showed it could hear airborne sounds far more effectively than through bone conduction alone.

-

The eardrum did most of the work. Jaw listening was secondary.

-

The size and shape generated enough vibration to move the ear bones and stimulate auditory nerves across multiple sound frequencies — meaning Thrinaxodon could detect a range of sounds, not just low-frequency ground vibrations.

How it works

Researchers at the University of Chicago scanned a Thrinaxodon skull and fed the data into Strand7, engineering software for bridges and aircraft.

-

They simulated how different sound pressures and frequencies would interact with the creature's anatomy.

-

They used material properties from living animals: bone density, tissue flexibility, ligament thickness.

-

The model revived a 250-million-year-old fossil.

“For almost a century, scientists have been trying to figure out how these animals could hear. These ideas have captivated the imagination of paleontologists who work in mammal evolution, but until now we haven’t had very strong biomechanical tests. Now, with our advances in computational biomechanics, we can start to say smart things about what the anatomy means for how this animal could hear.” —Alec Wilken, the PhD student who led the study

The backstory

For decades, paleontologists assumed Thrinaxodon heard mostly through bone conduction — pressing their jaws to the ground to pick up vibrations.

-

In 1975, paleontologist Edgar Allin proposed a wild idea: these creatures had primitive eardrums.

-

The theory made sense, but no one could test it.

-

Until now.

By the numbers

-

250 million years ago: When this hearing breakthrough happened

-

50 million years: How far back scientists pushed the timeline

-

3 tiny bones: Malleus, incus, stapes — the same ear bones humans use today, fused to Thrinaxodon's jaw but later separated to form the modern middle ear.

Zoom out

This creature lived during the early Triassic period, when mammal ancestors developed specialized teeth, improved breathing, warm-bloodedness, and likely fur. The eardrum was another crucial adaptation for survival alongside dinosaurs.

What changed

Technology caught up to theory.

-

CT scanning provided researchers a detailed 3D skull model, impossible with physical specimens alone.

-

Finite element analysis from engineering let them test a hypothesis from 1975.

-

The gap between "interesting idea" and "proven fact" was 50 years of waiting for the right tools.

“Once we have the CT model from the fossil, we can take material properties from extant animals and make it as if our Thrinaxodon came alive. That hasn’t been possible before, and this software simulation showed us that vibration through sound is essentially the way this animal could hear.” —Zhe-Xi Luo, PhD, professor, University of Chicago

It forces us to ask: what else did we get wrong about early mammal evolution?